Home » Progress Versus Tradition: Concept Bikes and Bike Design

Take a look at some of the bikes below; you’ll probably agree they’re pretty unusual.

We sometimes see alien bikes like these being showcased at a bike show, and wonder exactly what we’re looking at.

Which made us wonder…

In short, they give engineers the opportunity to take designs beyond where the industry is currently comfortable with the understanding that even if most of the features won’t end up making it to production, some will eventually. Or they’ll influence the development of other technologies elsewhere in the industry.

In the wider design world concept products and vehicles allow designers to step outside of their usual routine and experiment with ideas that may otherwise be ignored, helping to avoid the problematic Catch-22 situation of fostering innovation while reducing the amount of resource (time and money) that are spent pursuing dead-ends.

They also look super cool.

The Specialized fUCI concept bike, shown above in its mad glory, is case in point. It was created by Robert Egger, the creative director at Specialized, to challenge the conservative norms of the industry, and to show people what bike design is capable of.

Its name is a dig at the UCI and their strict rulebook influencing bike design. Although its designer insists it’s all in good fun, other voices in the industry don’t feel the same: in an interview with edp24 the famous bicycle designer Mike Burrows said that “anything that seems to make the bikes better is banned by the UCI. There is a negative set of rules which is not allowing progress within the sport and in terms of the bike”.

An Image source over at Road.cc gives some awesome further insights into the fUCI.

The outspoken Burrows is the man behind one of the most famous variations from accepted bike design, which made its debut in the 1992 Olympics and marked a change in Britain’s Olympic fortunes as a result.

His bike defies design expectations. The frame shape is different, the handlebars are incredibly low and promote a very aggressive riding stance, the solid back tyre is aesthetically striking, and the whole thing is incredibly aerodynamic.

After wowing crowds and winning medals, the UCI decided the bike was too far away from what was acceptable, and made the decision in 2000 to ban it – prompting the anger that Burrows has since expressed at the restrictive governing body which, in his words, means “the bikes have gone from superbikes and back to bicycles”.

The concept version of his bike was illegal within the UCI’s rules until 1990 because of its monocoque frame (referring to the material) – so it was nearly shelved before even seeing the light of day.

Before the Lotus 108 was banned, however, its success at the 1992 Olympics inspired USA Cycling (their team) to begin developing a bike of their own in time for the 1996 games.

Here’s what they came up with:

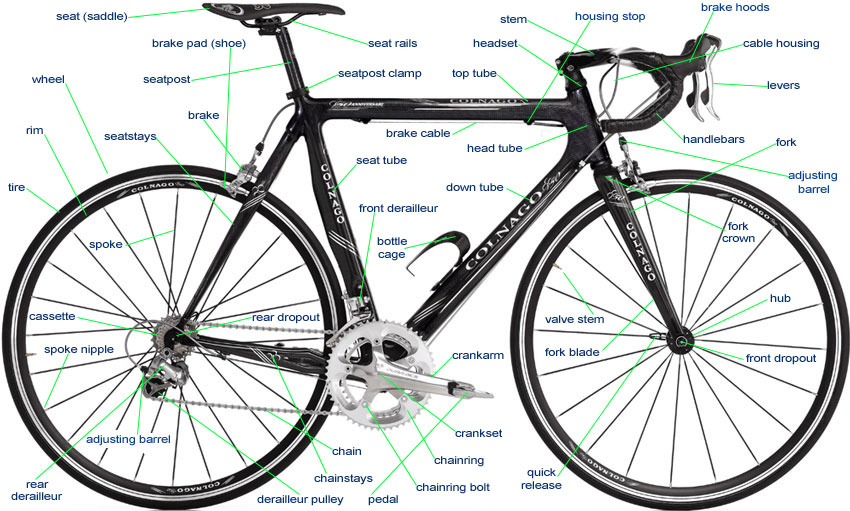

Its features fundamentally reimagine what it means to be a bike. Compare this bike or the Lotus 108 with the image naming the parts of a ‘normal’ bicycle, for example:

Some parts are skewed beyond recognition. Others – the top tube, the seatstays – are missing altogether. Many parts of this bike had to be custom built, and the ‘cockpit’ at the front was custom built for each rider.

It makes sense why manufacturers would hesitate to push the boundaries too far: imagine pumping thousands of pounds into the development of a new piece of gear or technology, and it to not get adopted. Or worse, to be arbitrarily banned.

One way of removing the financial risk of a new concept in cycling not being adopted is to crowdfunding. Sites like Kickstarter invite individual investors to contribute a much lower amount than a traditional investor in exchange for the product – and usually some extras – once it’s ready.

These sites come with the implied – but rarely emphasised – caveat that the technology might not work, as was the case with gyroscopic balance bike builders Jyrobike. Other times they take much longer than expected and the manufacturers have to reign in their expectations. But sometimes, they work and they bring a completely new technology to the market.

So we’re in the unusual position of having loads of innovation in the bicycle design space, but a governing body who are seen to restrict the influence this can have on professional cycling.

And while it may seem that professional and casual cycling can be kept separate, big manufacturers of components are less likely to invest large amounts of money developing products that will be banned from the lucrative professional market.

After having his bike banned by the UCI Burrows went on to develop others, and has created 74 across his career. The latest incorporates all of his design ideas throughout his career:

Will his prestige as a designer increase the likelihood of his quirky bike entering commercial production? Or is he destined to be trapped in the Catch-22?

Leave a Reply